A Mascot for Comfortable People trapped in the Apocalypse waiting for their Revolution to arrive already

This is a story about the deep limitations and possibilities of being a useless, over-optimized but mythical creature in the apocalypse.

When I was planning an exhibition in Baden, Switzerland with the organizers of Bagno Popolare in August of 2023, I was so excited to have been invited to make something for a cooperative peoples' spa powered by mineral rich thermal water. The people who contacted be had hijacked a natural resource (natural hotsprings) that had been privatized and secured only for the rich, and made it into a public amenity. I was so honored to be a part of this process.

Above is a pop up bath they made, siphoning the privatized water from the hotels that own the only rights to it, and sharing it with people on the street for free.

After centuries of the privatization of the thermal water by hotels in Baden, Switzerland (a city built for the wealthy and broken to come soak), the founders of Bagno Popolare began to siphon this water, delivered from the hot center of the earth, into free outdoor public pools. They made temporary guerilla peoples' baths all over the city. They showed films and organized cultural events around bathing to make it accessible to people who didn't know to want it. Eventually the city invited them to make two of these baths permanent. Bagno Popolare now maintains two popular free outdoor baths, that they built right in front of an expensive and corporate monolith called SPA 47.

This is the public bath in front of SPA47 which is built on top of a bath from the Middle Ages, as well as on top of what was most recently a public park. The location of this peoples’ bath feels like a little tiny revenge of the commons.

Based on the success of these public bathing interventions, someone gave Bagno Popolare a 1200 year bath under a hotel. They brought together 900 people to become members of a cooperative who would collectively run it, through working groups. So this spa called Bad zum Raben, inside the basement of a hotel in the bathing district of Baden. Unlike almost all spas, this one is organized by people who wanted to remake bathing as a social process, to skip the rhetoric of healing, as well as to peel off some of the layers of expensive sanitized individualist elite spa culture. They have opened up a space for a proletarian bathing culture in a place where that was forgotten since industrialization. I felt so honored to be brought into the process of opening, playing with and socializing the spa, through some kind of art intervention.

Here is a picture of me with Anna Lehr and Kathrin Doppler, the curators who invited me.

And, bmm bmm bmmmmmmmm! At the same time I felt very perplexed about what to do with this amazing opportunity. The world is burning, why would I make art for a spa, a sweet accoutrement for the most comfortable people on earth? Even people who appear working class in Switzerland enjoy the highest living standards on earth. Do I really want to make them more comfortable and healthy? I laugh as I say that. If you know my work, you may be familiar with the fact that I have never made anything comfortable in my life! October 7 passed and my confusion grew. The people I was working with from Bagno were smart, kind, doing good things. At the same time, no one spoke of the genocide(s) or of global water stress. They said, use the water!

This is a part of the spa that BP kept dry to use as a charming office as they brainstormed and mapped the future uses of the baths.

This is the reservoir that fills up each day with new hot water. Each hotel has a reservoir like this. The idea is that whether you use the water in the baths or not, it goes out into the river. So each hotel has a certain amount of water they have access to every day whether they use it or not. The white stuff on top is a thick layer of minerals. It's so thick that it hardens on the top to form a big sheet. It's filled with gypsum, which is what we make drywall out of. All the baths eventually turn white with mineral residue. Everything is foggy and smells like sulfur, like a strange mineral dream.

What could we do that would be significant enough to respond with respect, action and scale to a global crisis that is based on the genocide of a whole culture and people? "We" (me, my collaborators and the Bagno Popolare collective) were certainly the beneficiaries of the empires that produced the US and Israel, and the military industries that pretend to be our states. We certainly need healing, just as any children do when they have such horrible and abusive parents and extended families. What would be appropriate for us to do now while we are sitting in comfortable seats, in an emergency? How can we begin to acknowledge that this is OUR emergency?

Spoiler: I don't think we figured this out. What I realized is, I and we needed to change, but we don't know how. Nothing about how we work or live makes sense in a world that is changing for the worse for most living beings. I do not wish any harm to people, including myself, who live in relative comfort while others suffer. But I do wish that we could adapt more quickly to respond to the sacrifices made by a world built to serve us, even if we don't want what they made for us.

I walked by this traumatic baby fountain each day on my way to the bath. Why do they have so many muscles?

Baden is a city founded to heal the elite. It was a spa town since the Roman Empire, and that history is incredibly close to the surface. When I sat alone in the bath during my August visit, as pieces of the wall crumbled into the water, I was looking at rocks and mortar that were many hundreds of years old. A few years ago, while digging to build a parking lot underneath a new corporate spa, they found a bath from the Middle Ages. If you ask at the front desk of the SPA 47, you can go to the parking lot and see it.

I visited the Baden State Museum, where I found a 2000 year old mosaic with images of mythical hybrid animals, from the cold water room of a bath house near Baden. The mosaic was a relic from the Roman Empire and was under glass. It looked familiar to other mosaics I've seen in other bath houses, with hybrid animals on them. There is even one in the Stadtbad Neukolln in my neighborhood, in Berlin.

This is the mosaic I found at the museum. It has several different kinds of hippocampuses. I love this one, which appears to be a bull, a chicken, and a fish. This is the hippocampus I identify with the most, which is what I based one of the mosaics on.

Here is an image of the Roman baths that were located just behind where Bad zum Raben is now located. People would be in the dirty water together, eating and wearing a lot of fabric. There were baths for rich people and for poor people, so it was not exactly liberated.

A Hippocampus is a mythical hybrid animal with a horse, cow or goat in the posterior and then a fish or a snake anterior. It's called the hippocampus, which is also a word that gets used for a seahorse. A seahorse is a hippocampus, (for humans, a seahorse is one of the queerest animals ever because the males are the ones who reproduce). I suggested to Cat, one of the curators, that I would like to make a mosaic for the peoples' bath. I love the idea of communal luxury, and somehow, a new mosaic felt like it would elevate the bath house to some kind of deluxe ancient permanence. I also liked it because Bagno Popolare organizers told me that they really aimed to recreate some of the culture of the Roman baths, when people would be together in the same (dirty?) water.

When I was proudly planning to make a mosaic for this anarchist cooperative bath house, I was drawing the hippocampus, and so I was really looking at the shape of the body. When I first looked at it, I assumed that it would be the kind of organism that would be able to survive in all conditions, a real all-terrain animal. Due to the fish tail and the hooves on many of the images, I assumed that the hippocampus could live in water or on land. What a dream. But the more I drew it, the more I realized that it was possibly an over-optimized animal. I imagined what it would be like to get in the water with hooves as front fins, and I realized that it wasn't gonna get very many places in the water. And maybe worse, what would it be like to drag a huge fin across the sidewalk with just two hooves? So this kind of all terrain organism actually seems like it has a pretty hard life on land or water, even though it has the signs and symbols that could indicate an all terrain survival. While it could live anywhere conceptually, in practice it seemed like a being that could be permanently homeless.

This is a bad painting I made, but it helped me realize what a big tail there was to drag with just two front hooves.

The more that I drew and thought about it, the more I started to invent ways that this being could exist, easier. Like what if it had a bathtub with water in it, on wheels? This way it could drag its tail behind it using its front hooves? What if we put fins over the hooves like the ones that I wear when I swim? Could it live along coasts, or in bath houses? It would definitely have to live on the edge, where the normal rules don't apply. Ultimately, what I realized is that I really relate to the hippocampus, in its belonging, which is to an impossible edge, that exists everywhere and nowhere. As my friend Sandra Huber told me about my own liminal state of being, maybe we are littoral animals, edge riders, high needs bottom feeders.

I also feel like I've been over optimized. I've been so educated. I can think my way through so much and I've been led to believe that I can do anything. But when it comes to the real conditions of our shared reality in the apocalypse of genocide, war and environmental collapse, how good am I in a fire? How ready am I for a real emergency? What kind of exhibition will save us from running out of water? So what I started to think about was, how the hippocampus could be our mascot for the privileged.

And isn't it kind of nice to have a mascot? Like at least we know that we are something. We are neither nothing nor everything, if we have a mascot. We're not nothing because we can see how we scrape our soft undersides along the sidewalk when we walk, and how our front half sinks awkwardly in water. We are not everything, because in fact, we are just actually very weird in our overspecialization.

I planned to make some mosaics when I returned to Baden, and I didn't tell the curator or the preparator that I had never made one before (or that I am a conceptual artist who doesn't really make anything). When I arrived, I visited some hotels which were built on top of hot springs hundreds of years ago. These hotels now completely own all access to the healing water. The curator, Cat, made a contact for me, so I could be brought to the basement of some of these hotels. Over the past decades, each hotel had been renovated to look more slick and white and sanitized. This is funny since the water is very cloudy, even grey with hot minerals. So I visited the hotels to see the old tiles that had been removed and replaced by something even whiter. I collected the old tiles, which had been sat on for decades, by wet rich people. I carried very heavy boxes filled with this 1970s spa decor to Bagno Popolare, where I smashed them in the foyer with a hammer. Sometimes members of the working groups would come, and while they were meeting or testing the water quality, they would hear me smashing tiles and screaming. I began to produce two mosaics out of these tiles, both of hippocampuses– one based on the mosaics in the Baden Stadt Museum, and one based on Harry Potter.

I spent about two weeks making these two mosaics. Smashing, and rebuilding out of rubble. It felt like a kind of cathartic somatic abolition practice. Destroying something as we also make new shapes out of the destruction. I attached the broken pieces of elite healing to a thick hard foam using cement. I built, made mistakes, started again several times. I asked myself many times why I was doing this. I worked until two days before the exhibition opened. We were going to place the hippocampuses in the baths, but we didn't know what would happen in the very thick hot water with very fresh mosaics. Would the mosaics fall apart?

Here we can begin to describe what it means to be comfy in the apocalypse with way too many ideas, skills and ways of doing things that simply don't apply to the real conditions. The amazing contradiction of accidentally making a self portrait in Switzerland, in an apocalypse, is not lost on me. The night of the opening, I left the bath house to go home and change into a suit and tie. I started to think about the hippocampus as me and me as the hippocampus, sweating in my business suit at the bath house. I arrived, and walked to the bath where the Harry Potter Hippo would be swimming, hoping for the best in human mosaic relations. First I saw a man with a large belly, looking at his phone with a beer in his hand. I walked closer to see that he was gently nudging the hippocampus across the water with his toe. The mosaic was floating.

This is what I thought we would do with the mosaic.

This is where it ended up.

One of the curators, Anna, helped me pick the wet body out of the pool and put them on the floor. We walked them into another room in the spa. In this room, I had designed a cathartic process, where visitors could come and throw plates into an empty bath while screaming. Above the bath there was a statement: I am willing to lose/destroy my x if it helps us get closer to y.

In this image you can see that I am completely out of my mind. Photo by Magda Hartelova.

Each visitor signed a contract, and wrote on a plate what they are willing to lose or destroy on our way to something collectively necessary or desirable. We placed the hippocampus at the bottom of the bath where the plates would be thrown. It felt like a weird sacrifice. This mosaic had become so precious to me, what if I let people throw stuff at it? Would it be possible that people would be able to participate in destruction while protecting something delicate? Isn't that how abolition will always work? And it forced me to rethink what was precious about this sculpture. Was it the object itself? Was it what I learned on my way? Is it ok to hold onto precious stuff

?

These are the broken plates that covered the hippocampus at the end of the exhibition. It was as if it was composted by other people's feelings of powerlessness and privilege.

To intensify things, I went to the other bath, my favorite room in the little spa. There I had worked with the light so it looked like there was a full moon in the room, and the water sparkled above the other hippocampus mosaic, which lived in the water. Just as I walked in, the second hippocampus was being lifted out of the water with one hand by another man with a beer. In German he said that there wasn't enough room for him and the mosaic in the same bath. I laughed and I pretended that I didn't mind that he tossed the "art" onto the floor.

Someone came to get me. It was time for the opening presentation for the "vernissage", and I was to lead a tour of the 6 room installation I made. The overall installation was called The Social Spa for Collective Mutation. Each room had an action and a physical installation that would help visitors of the spa to change in collective, embodied and unconscious ways. The subtitle of the spa was "a place you can go when you know you need to change but you aren't sure how." When it was my turn to talk, I couldn't remember why I was there or what to say. I asked someone to hand me the brochure for the project, so I could remind myself. I was wearing a suit and tie with bare feet, I was sweating.

I didn't know what to do, so I stepped into the hot water where the first mosaic was meant to go. I stood there with my wet paper, my suit half submerged. I looked around at the people in the water, mostly strangers drinking beer, annoyed that I was interrupting their conversations. In this room, I had proposed that we only ask questions. I asked the people in the water, and the dry people who were here for the art to start by asking questions. It was incredibly hard and dry given the wet heat of the room. I got bored with the clogged conversation and I said,

"There was supposed to be a mosaic in the water. It is a mosaic of a hippocampus. The hippocampus is a creature that should be able to live anywhere. It has a horse in the front and a fish in the back. But when we put the mosaic in the water, it floated, so we took it out. I feel, and I fear, that I am here as the mosaic and as your hippocampus. I neither sink nor float. There is nowhere I really belong, by the sea or in the city, and certainly not here. I'm too smart to do anything but I don't know how to do anything that matters materially in the world. I am made of broken pieces of empire that don't exactly fit together. And I crumble easily."

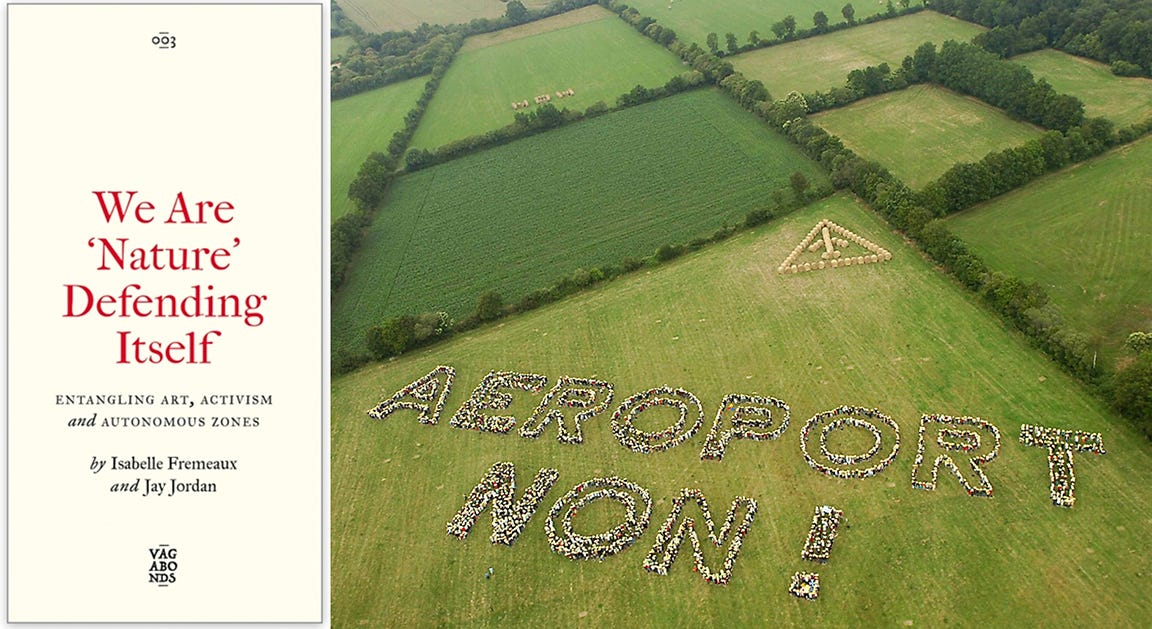

I returned to Berlin, and was excited to hear a friend was in town from France. Jay had co-written one of my favorite books with Isa Frameaux called We Are Nature Defending Itself. Jay is an artist that I heard about through rumors, about direct actions they were a part of with Reclaim the Streets, long before I ever met them. They work collaboratively, with an art of large scale organizing and big humorous political interventions in a way that has actually changed the world. So I was sitting with Jay Jordan at my favorite Greek cafe in Berlin.

They had just been a part of a documentary that had received a prize at the Berlin Berlinale, and Jay was sharing the gossip about it. Then I began to talk about a new book that I had just submitted a proposal for, called the The Flat White Dimension: Working within the Confines of Comfort in the Apocalypse. To try to summarize the vibe of the book, I described to Jay the hippocampus, our mascot. Just then, Jay turned their forearm so I could see it, and an image of a seahorse.

"I have a hippocampus".

Jay told me that they became a hippocampus during their first and last Ayahuasca ceremony as a 40th birthday gift. I almost died! They mutated during a deep dive trip in a dingy beer smelling night club in East London led by a DJ shaman. Years later they realised that they had not listened to the plants' advice at all. The hippocampus was shouting “you are queer, come out of that horrible closet!” Jay waited till they were 55 before coming out as non-binary. The sea horse is an often used symbol of non-binaryness, due to the males carrying the babies. The ritual invited them to transition away from an identity and body of a CIS male, to become more. The hippocampus appeared as a being that did not have to choose, that could be liminal, that could be many things. And the hippocampus represents a kind of beauty to Jay, and Jay is such a gorgeous hippocamp.

Below you can hear Jay talk about the hippocampus and transitions:

I got quiet. Jay's story really affected how I began to see myself and how I began to see the hippocampus.

It took me a month after the vernissage to get back in touch with Bagno Popolare, to ask about the hippocampuses, to send invoices, to find out about the show. I was afraid of what may have happened to the mosaics, I didn't want to hear that the show was too weird, I felt like I had not produced the transformation I promised. Most of all, I was afraid of my own attachment to this stupid art! Not out of any malice, one of the curators told me they don't really want to keep the mosaics. One of them was destroyed beyond what they would repair. And because they didn't want to install them permanently, they floated instead of sunk.

And so I was looking for somebody who would take the mosaics. After speaking to Jay I realized that the mosaic could represent so much more than privilege, if privilege is an idea that is (incorrectly, I would say) tied to power as well as to guilt, uselessness and immutability. But now, I realized that they could represent the possibility of liminality, of being more than one appears, of being many things at once. Not having to participate in binaries or exclusively identify as one thing or another thing IS a privilege, but it might be one to want instead of one to feel shame about.

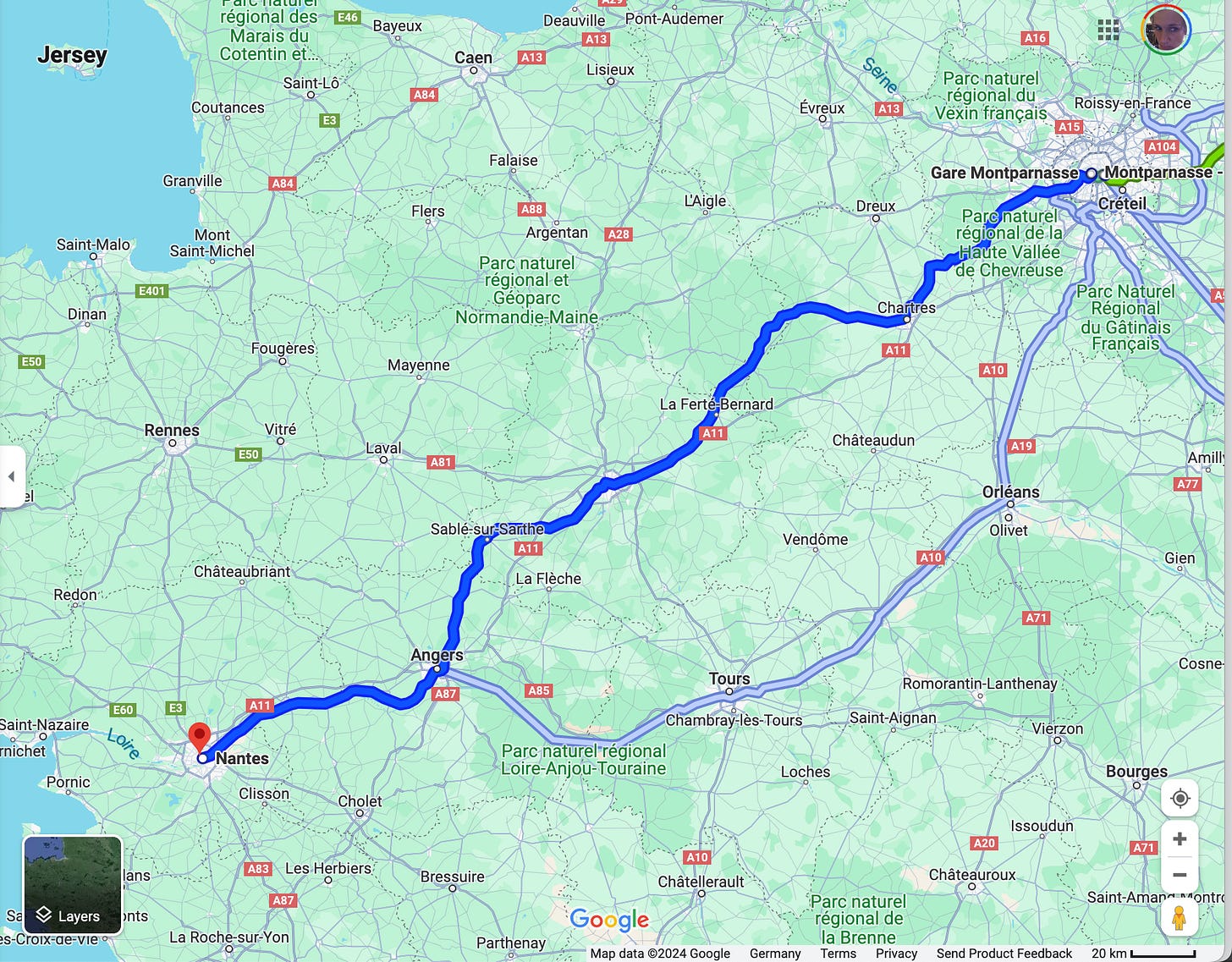

Jay lives on the ZAD in France, an occupation of land that France attempted to turn into an airport for Nantes. I've spent the last couple of years learning about the ZAD because it represents one story of what it means for people to organize to live outside of property ownership; to do this and more, against the most violent arm of the state. And they did it. I asked Jay if I could bring that mosaic to their home on the ZAD and put it in the garden. It would be like an accessory that goes with the beautiful tattoo and transition, and she said yes. So I did that. And I am waiting to find out if the mosaic floats on wet communal land.

Jamie Allen and I took the mosaic to the ZAD on the train.